Universal genius, superlative inventor, masterful painter… The whole world is celebrating the Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci on the 500th anniversary of his death. But was he really a major pioneer of engineering? Attendance at a conference hosted by the RWTH Aachen University offered a rather sobering view.

“Leonardo Worlds: Yesterday – Today – Tomorrow”. This was the title of a commemorative colloquium hosted by the RWTH in the Super C to honour Leonardo da Vinci. For one evening and a whole day, scientists from a range of disciplines approached the phenomenon of Leonardo, his methods and his inventions – and the question of which of all his achievements are still useful for researchers today.

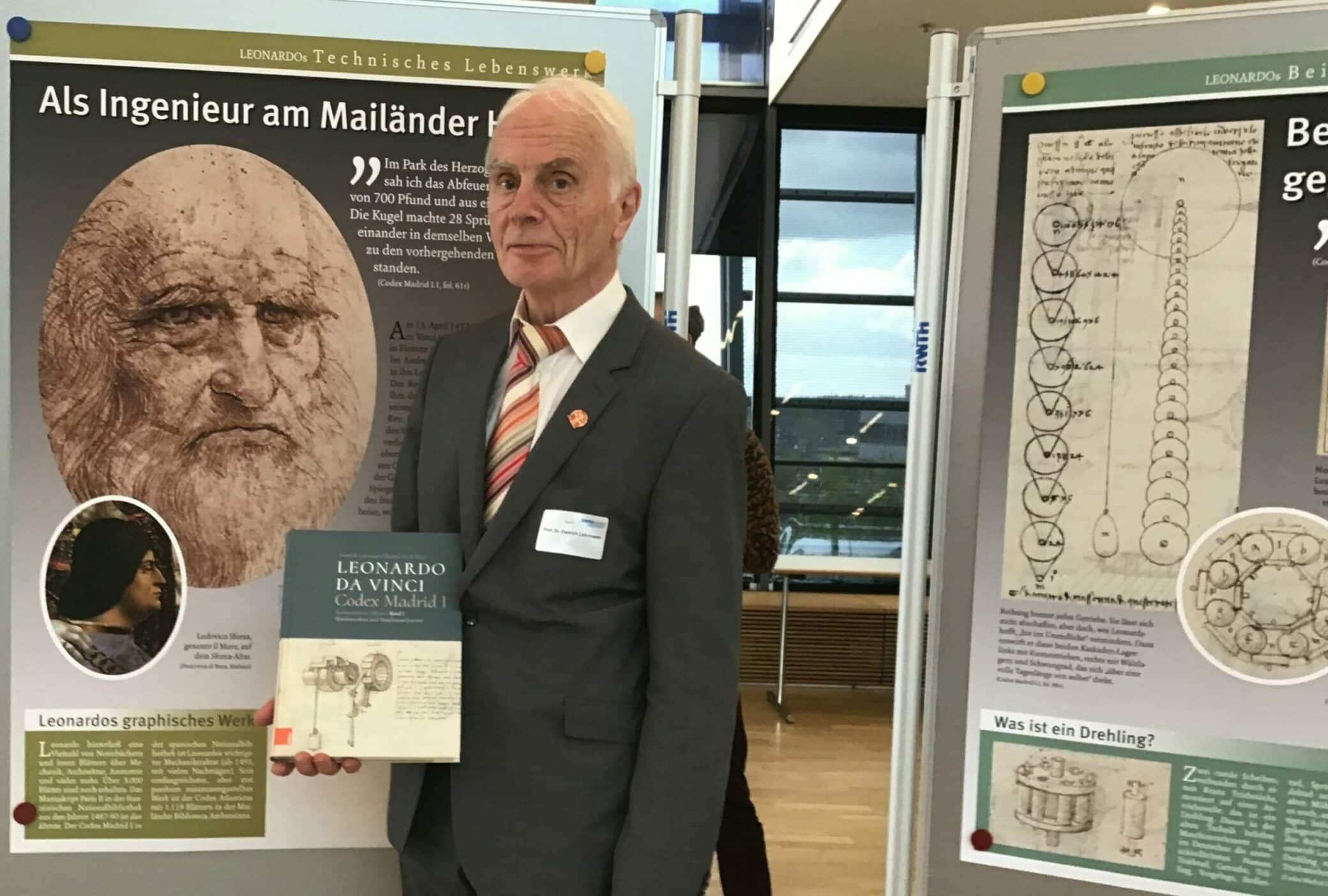

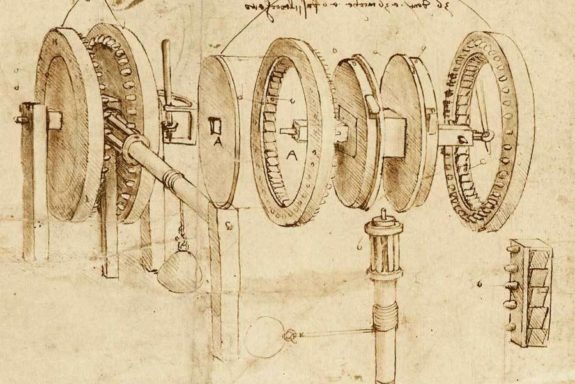

What was of particular interest at the conference was that a historian of technology had focused on a part of Leonardo’s legacy and edited it in such a way that we can now finally really understand what the highly acclaimed genius was actually thinking. The “Codex Madrid I”, which dates from 1493-95, is Leonardo’s magnum opus on mechanics. In the framework of a project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), historian Dietrich Lohrmann and his team spent four years deciphering, analysing, sorting and ultimately commenting the work. A Herculean task, when you look at the pages full of disorganised scribbles and scrawls: notes in mirror writing, sketches and design drawings that often do not even bear the slightest relation to each other.

An icon falls from his pedestal or a genius is deleted

So what did Lohrmann and his team find out? That Leonardo was nowhere near the genius he is assumed to have been. In the contrary, he studied machines that already existed and copied design drawings from books – admittedly with the intention of improving on them. His famous armoured fighting vehicle, for example, came from an engineer by the name of Valturio. Unfortunately, Leonardo’s own enhancements actually “disimproved” the original war machine. His hand-powered cranks transmit the movement in such a way that the wheels would turn in opposite directions to each other. This would result in standstill or transmission damage. Not to mention the question of how a heavy armoured vehicle carrying canons and a crew could be set in motion by hand-powering just two cranks. By the way, these were not the only “enhancements” Leonardo came up with that would have rendered the invention incapable of functioning in the real world.

He never built a prototype

Leonardo never once built a prototype; his drawings were never compiled. The Codex Madrid was only rediscovered by accident in 1965. In a radio interview with the German World Service gave the following summary: “Leonardo the genius is an invention of the 19th century, a period of history in which rapid technological advances were being made and Leonardo was idolised as a kind of progenitor of this promethean philosophy. If we now look at what he really left us, he becomes a completely normal, albeit highly motivated and very industrious observer of the technology of his times, one who understands it all and wants to improve it. But it’s hard to find anything that is radically new. Everything can already be found in older engineering manuscripts. So, suddenly, the genius is actually just a normal man of the Renaissance era, who – among the many other prominent people of his times – did not play such an extraordinary role.”

Only Leonardo da Vinci’s masterful paintings remain as the legacy of a genius, even if he did not actually get round to finishing many of them.

Leonardo da Vinci: Codex Madrid I

Commented Edition

Dietrich Lohrmann (Ed.), Thomas Kreft (Ed.)

250.00 Euro

1,243 pages, with 375 col. facsimiles and 26 col. illust.,

4 Vols in a slipcase,

ISBN: 978-3-412-51206-4

Böhlau Verlag, Cologne

In German

08.05.2019